The "Economics" Of Individual Liberty

And The Second Amendment

By L. Neil Smith, lneil@netzero.com.

The Libertarian Enterprise. December 13th 2013

Prepared for Jews for the Preservation of Firearms Ownership. © JPFO. Inc 2013

The late, unlamented twentieth century will be remembered in the future, principally for two things, the two biggest, most destructive inter-governmental conflicts in history, and the number of innocent individuals (more than 100 million) slaughtered wholesale by their own governments.

For anyone with two gray cells to rub together, this is the final, inarguable proof of the dire necessity of the people to keep and bear arms.

The twentieth century was also the century of socialism, a school of political economy which asserts that the interests of a single individual are of less importance (if they're of any importance at all) than the interests of the group, whoever the group turns out to be. Those who successfully claim to speak for the group are then free to do anything they wish with the life, liberty, and property of the individual.

The twentieth century was also the century of socialism, a school of political economy which asserts that the interests of a single individual are of less importance (if they're of any importance at all) than the interests of the group, whoever the group turns out to be. Those who successfully claim to speak for the group are then free to do anything they wish with the life, liberty, and property of the individual.

Socialism has never been limited to Russia and China, or a few European or Asian nations. Wherever the interests of the individual are sacrificed to those of the group, there you have socialism. The great libertarian philosopher Robert LeFevre maintained that, to any extent a society has any public sector" at all -- funded by wealth taken by force or the threat of force from the individuals who created it, in violation of their rights -- to that extent it is a socialist society.

Those three signature phenomena of the twentieth century, widespread war, slaughter, and socialism are not unrelated. Under socialism, mass murder and other such atrocities are inevitable and unavoidable, much like the law of gravity, and the sun rising in the east.

Here's why:

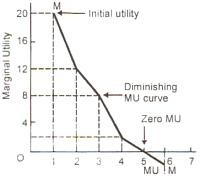

There is a fundamental observation within the field of economics called the "Law of Marginal Utility". The concept is highly important to human survival, prosperity, and progress; among other things, for uncounted thousands of years, it has made peaceful trade possible among killer apes. It isn't really a law -- economics isn't really a science -- and it actually has more to do with psychology (which is not a science either) than it does with anything else. The Law of Marginal Utility is a statement about the way people look at certain things.

It works like this: Marginal Utility holds that the more you have of any one commodity, the less value you tend to assign to any single unit of it. Imagine you're a Paleolithic hunter who just killed and cut up an aurochs, a sort of giant prehistoric longhorn cow, yielding around 3000 pounds of meat that you now have to do something useful with.

It works like this: Marginal Utility holds that the more you have of any one commodity, the less value you tend to assign to any single unit of it. Imagine you're a Paleolithic hunter who just killed and cut up an aurochs, a sort of giant prehistoric longhorn cow, yielding around 3000 pounds of meat that you now have to do something useful with.

A friend, who has also just killed an aurochs, and now has the same problem you do, drops by offering you a couple of pounds. You can remember hard times in which two pounds of meat might have meant the difference between living and starvation, but you politely turn him down.

In fact, when a second neighbor visits, complaining that he doesn't have enough meat to feed his kids, you give him some of yours because it isn't that big a deal. You have so much you'll never get around to eating it all. Of course you can't do this for everybody, or you won't have anything left for your own family. But that's a political problem for the future. Just now you ask him not to tell anyone about your generosity.

Yet another neighbor, who prefers gathering to hunting, drops by, griping that this year's yield of beebleberries was so abundant that she now has baskets of the damn things she doesn't know what to do with.

One of you gets a bright idea: swap some meat for beebleberries. What makes it a bright idea is that you have so much meat, you value any particular pound of it less than your neighbor, who has no meat. Your neighbor, on the other hand, has so many beebleberries that she values any particular basket of them less than you do, who has no beebleberries.

This is the Law of Marginal Utility at work. I makes possible an exchange of valuable commodities in which everybody wins. (Marxists would insist that such a thing is impossible, that one of you must have exploited the other somehow, but they won't be able to tell you which.)

By now, you're probably wondering what all this has to do with the individual right to own and carry weapons. In this connection it's very important -- in fact it's the whole point of this essay -- to understand that there are certain commodities to which this "law" doesn't apply at all, mostly because they aren't really commodities. Any pound or basket of them is not exactly like any other pound or basket.

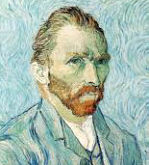

An example that comes to mind (to my mind, anyway), is original paintings by Vincent van Gogh. If I had a hundred of them, that would not reduce my desire or regard for the hundred and first, because they are in no way interchangeable. Each is absolutely unique. And we would properly regard anyone who bought and piled Van Gogh paintings up like cordwood, and measured their value by the height of the pile, as a barbarian.

An example that comes to mind (to my mind, anyway), is original paintings by Vincent van Gogh. If I had a hundred of them, that would not reduce my desire or regard for the hundred and first, because they are in no way interchangeable. Each is absolutely unique. And we would properly regard anyone who bought and piled Van Gogh paintings up like cordwood, and measured their value by the height of the pile, as a barbarian.

Human lives are like paintings by Vincent van Gogh. Each and every one is absolutely unique -- more unique, if possible (grammatically, it's not supposed to be) than even the finest, rarest work of art. And there are more reasons to come to that conclusion than can possibly be counted.

But they can be estimated.

To begin, each of us is genetically different from one another, each of us the result of billions of possible genetic permutations and combinations. Although we tend to resemble our parents and their parents in many ways, each generation is a fresh roll of the genetic dice.

It's a lot better than simply splitting like an amoeba, resulting in two organisms with identical genetic complements. A species whose members bring a slightly different set of attributes to the problems life presents them with has a better chance of surviving longer. Once nature's "got your number", as it were, uniformity (or conformity) is death.

So we all differ from one another genetically.

Each of us, as well, has had a lifetime of different experiences, which have imprinted themselves on our personalities, altering them, helping to make us precisely who and what we are. Moreover, each of us regards each of those experiences in different ways, attaching, either consciously or unconsciously, different levels of significance to them.

Thus we all differ from one another in our experiences.

Thus we all differ from one another in our experiences.

Finally, we are all the result, in part, of things we have chosen to do, say, think, and, to a degree, feel -- all acts of free will, which Ayn Rand said consists of only one choice: to focus the mind or not to focus it. How many times has the average individual made such a choice?

We all differ from one another in our choices.

Now, multiply the number of genetic possibilities times the number of different experiences we've had (and the ways we've interpreted them), times the acts of free will that have shaped us. For all practical purposes, the ways in which each of us is unique approaches infinity.

Each individual human being is absolutely unique, and vastly rarer -- and more irreplaceable -- than the rarest work of art. Thus it is a basic tenet of the Austrian School -- the heart and soul of the study of free market economics -- that you can't quantify human beings or their behavior, and that mathematics, especially statistics, is sadly inadequate to the task of understanding what people do or why they do it.

Now here's the thing: socialists don't see it that way. To them, statistics is the key to understanding history and human nature. Human beings are just like batteries to them, or bottles rolling off an assembly line somewhere, In a world of seven billion human beings, in a nation of 330 million, Marginal Utility rules. Any given individual counts for nothing. With a little training, any human being can be unplugged, discarded, and replaced by practically any other human being.

When human beings come to be perceived, by socialist politicians, by socialist bureaucrats, by socialist policemen, by socialist judges, by socialist academics, and by socialist media, as nothing more than indistinguishable, interchangeable units of a commodity, then any public manifestation of individuality -- let alone individualism -- is seen as a threat to be managed. So terrifying do they find it, that they have spent billions of dollars and millions of man-years in order to delegate the recognition and acknowledgment of individuality to machines.

Little wonder that, when the socialist elite decide that not enough of those seven billion units are serving socialist interests, they come to the conclusion that the great majority of them can be discarded. It happened in Armenia, in Nazi Germany, in Soviet Russia, in Red China, in Pol Pot's Cambodia, and it was almost always preceded by sweeping gun confiscation -- or to a population already long since disarmed.

Little wonder that, when the socialist elite decide that not enough of those seven billion units are serving socialist interests, they come to the conclusion that the great majority of them can be discarded. It happened in Armenia, in Nazi Germany, in Soviet Russia, in Red China, in Pol Pot's Cambodia, and it was almost always preceded by sweeping gun confiscation -- or to a population already long since disarmed.

Little wonder, too, that the idea that vast numbers among those seven billion indistinguishable, interchangeable units -- mainly the 100 million Americans who own "750 million firearms of modern design, in good working order" -- might not want to be discarded, and are capable of successfully resisting it, fills socialists with fury and terror.

Now I'm not really an economic determinist, but you need very little else besides the so-called "law" of Marginal Utility to understand and explain the inexpressible horrors of the twentieth century.

Or the compelling need for each and every one of us who refuse to see ourselves as "indistinguishable", "interchangeable" units to be equipped to defend our "insignificant" and "thoroughly expendable" lives.

Author and lecturer L. Neil Smith is Senior Editorial Consultant for Jews for the Preservation of Firearms Ownership. A fifty-year veteran of the libertarian movement, he is the Author of 33 books including The Probability Broach, Ceres, Sweeter Than Wine, And Down With Power: libertarian Policy In A Time Of Crisis. He is also the Publisher of The Libertarian Enterprise, now in its 17th year online.

Visit the Neil Smith archive on JPFO.

© Copyright Jews for the Preservation of Firearms Ownership 2013.

![]()